Humanist modernity. Stanisława and Maciej Nowicki

Intro

Stanisława Sandecka-Nowicka and Maciej (Matthew) Nowicki are two significant figures in the history of American and Polish architecture.

She was a talented graphic artist and designer and the first female professor of architecture in the history of the United States. He collaborated – despite his young age – with renowned architects on prestigious projects whose implementation was interrupted by his tragic death. Their story is a fascinating tale of creative passion, their life together, and the possibilities and limitations of the turbulent beginning of the 20th century. The dramatic history of their homeland, their lived experiences, but also a great hope for a better future laid the foundation for an innovative curriculum and architectural designs that changed the history of the profession. By combining the latest building developments with great respect for the local context, their readiness for dialogue and understanding of others, as well as their enormous talent, they created a humanistic modernism that opened the contemporary understanding of architecture to previously unknown realms.

-

Stanisława Sandecka-Nowicka, photo by George Pohl © University of Pennsylvania -

Architectural Planning of United Nations Headquarters, Matthew Nowicki, © UN Photo, New York, 1947

Maciej Nowicki

Maciej (Matthew) Nowicki (1910–1950) pioneered an innovative approach to architecture that derived aesthetic expression from structural engineering, broadening the understanding of both disciplines.

Matthew’s interest in drawing blossomed during his visits to the Art Institute of Chicago, where his father worked as consul general after Poland regained independence in 1918. Upon his return to the country, Matthew began studying fine arts in Krakow and then architecture at the Warsaw Polytechnic. He married the architect Stanisława Sandecka, with whom he established an architectural practice.

The couple withstood the difficult circumstances of World War II. Matthew remained professionally active in secret architectural competitions, taught masonry, and worked as a design lecturer in the underground classes of the Warsaw Polytechnic, even though teaching architecture to Poles was banned by the Nazis.

After the war, Matthew returned to his work through planning for the reconstruction of Warsaw. He later traveled to the United States as cultural advisor to the Polish diplomatic mission and was involved in the design of the United Nations headquarters in New York. He was appointed the first director of the School of Architecture at North Carolina State College.

Nowicki died tragically in a plane crash caused by an engine fire above the Libyan Desert in August 1950.

If time had allowed his genius to spread its wings in full, this poet-philosopher of form would have influenced the whole course of architecture as profoundly as he inspired his friends.

Eero Saarinen 1910–1961, Finnish-American architect and interior designer, one of the most prominent figures in American architecture of the 1950s.

Stanisława Sandecka-Nowicka

Stanisława Sandecka-Nowicka (1912–2018) was the first woman in United States history to receive the title of professor of architecture. She began her career as a student at the Faculty of Architecture at the Warsaw Polytechnic, where she met her future husband, Matthew Nowicki. Parallel to her architectural activities, she worked as a graphic designer.

Stanisława and Matthew signed their designs with a joint signature. In addition to posters, their works included leaflets and illustrations, as well as interiors, for example, for the Polish pavilion at the 1937 “International Exposition of Art and Technology in Modern Life” in Paris. Upon receiving a scholarship from the French government, Stanisława spent a year working with Le Corbusier on a photo collage for the “Temps Nouveaux” and a stadium design, among others.

After the war she worked in the Bureau for the Rebuilding of the Capital creating plans for the reconstruction of Warsaw. She co-authored the designs for the Resort Hotel in Augustów and the Paraboleum in Raleigh. In 1950 she worked with William H. Deitrick on the interior designs for the Carolina Country Club. In 1951, Sandecka-Nowicka began her academic career at the University of Pennsylvania. After receiving the title of professor in 1963, she was often referred to as the grand dame.

Stanisława Sandecka-Nowicka was awarded the Medal of the American Institute of Architects in 1987 and the Gloria Artis Medal in 2016 for her contribution to Polish culture.

Beginnings

The joint design venture of Stanisława Sandecka and Maciej Nowicki began in 1931, when – as students – they established a studio for interior and graphic design. Their first commission was to design interior decoration and printed materials promoting the annual Architecture Ball at the Warsaw University of Technology. Between 1931 and 1936 they created about 20 poster designs. For their designs, they received numerous awards, which recognized their technical prowess and artistry. As students, Nowicki and Sandecka participated together in architectural competitions for various buildings, such as the Warsaw Mosque, in which they placed third (1936) or a spa house in Druskienniki, which they won (1938).

Notable among their projects is the Resort Hotel in Augustów (designed together with Władysław Stokowski), completed in 1938. In the US they worked on the design of the Dorton Arena and the interiors of the Carolina Country Club in Raleigh (together with William Henley Deitrick).

In addition to his large-scale and largely unbuilt visions, Matthew Nowicki’s architectural work consisted of many smaller commissions, in which he often collaborated with Stanisława Sandecka-Nowicka. They participated in many architectural competitions. In 1938 Nowicki worked with Jan Bogusławski on his design for the Polish pavilion for the World Fair in New York.

During the war, Nowicki worked conspiratorially and actively participated in architectural competitions with other architects. In the post-war period, Nowicki had the opportunity to further develop and publish some of the projects he had started in Poland.

While continuing his work with Harrison on the UN headquarters in New York, Nowicki began collaborating with architect Clarence Stein. They designed a circular, elevated platform for pedestrians at Columbus Circle in the northwest corner of Central Park. He worked on many projects in North Carolina as a consultant for William H. Deitrick’s firm.

Warsaw

The German attack on Poland in September 1939, carried out in cooperation with the Soviet Union, brought the entire country under occupation. During this time, the population of Warsaw was estimated at over 1.3 million inhabitants.

Warsaw was one of the cities most affected during World War II. About 85% of the left-bank part of the city was destroyed. Infrastructure losses included all bridges over the Vistula River, 90% of industrial buildings, 90% of architectural landmarks, and over 70% of residential buildings. 70% of schools and 95% of cultural buildings were damaged. The railway and tram systems ceased to exist.

Braun Sylwester alias Kris, 1944 © Museum of Warsaw

Rebuilding Warsaw

Postwar Warsaw was a sea of rubble. However, on January 3, 1945, shortly before the Red Army reached the city, the Provisional Government in Lublin decided to rebuild Warsaw. To coordinate this gigantic effort, the Bureau for the Rebuilding of Warsaw was established. The extraordinary character of Warsaw’s reconstruction can be attributed to the vision of Jan Zachwatowicz, who strove to completely rebuild all of the destroyed historical buildings. Of the 957 buildings that were listed as monuments before the war, only 34 survived the war in good condition.

In 1980, UNESCO placed Warsaw’s Old Town on the World Heritage List. It was the first time this distinction was given to a city that was completely rebuilt.

Nowicki’s designs

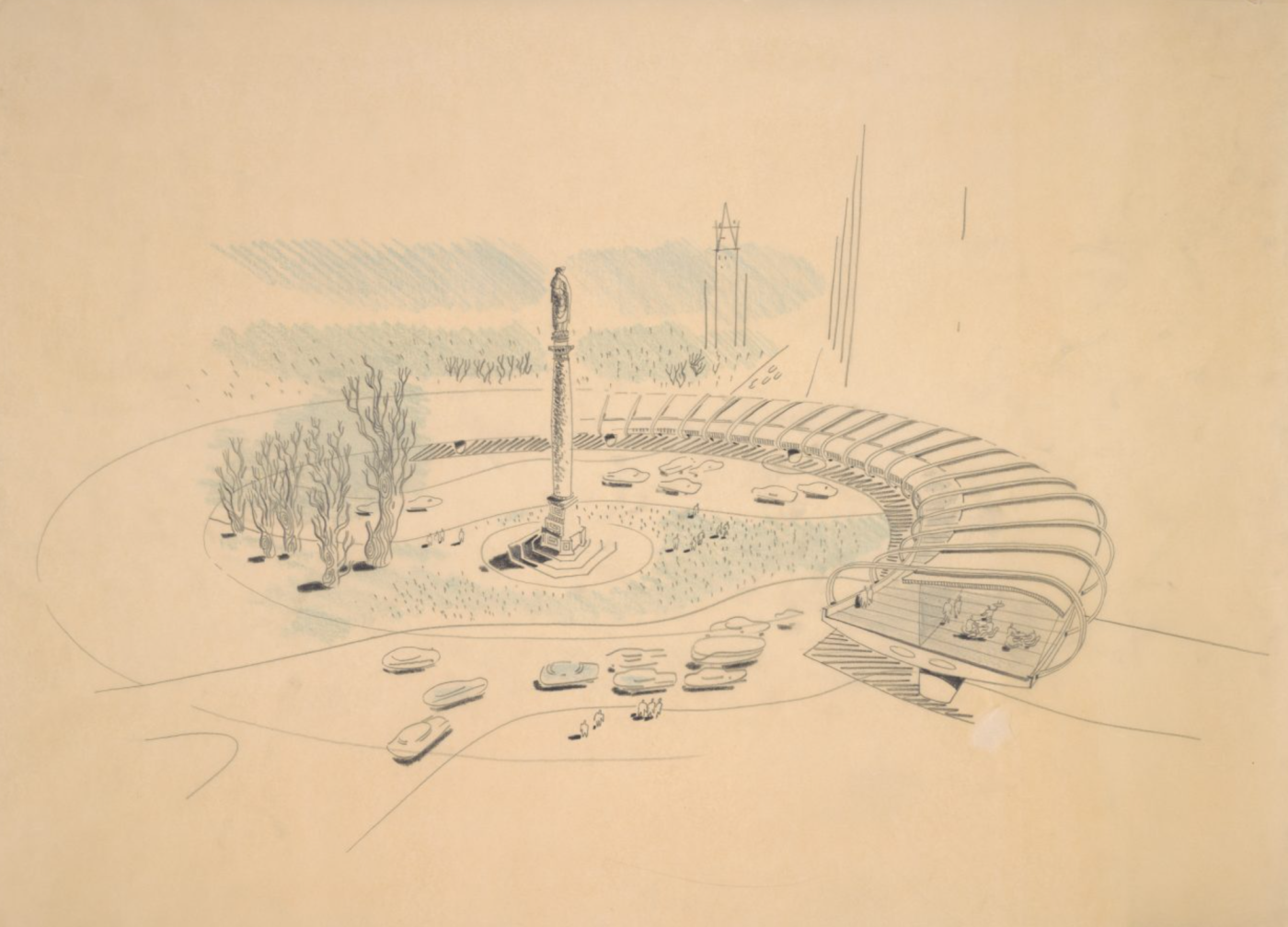

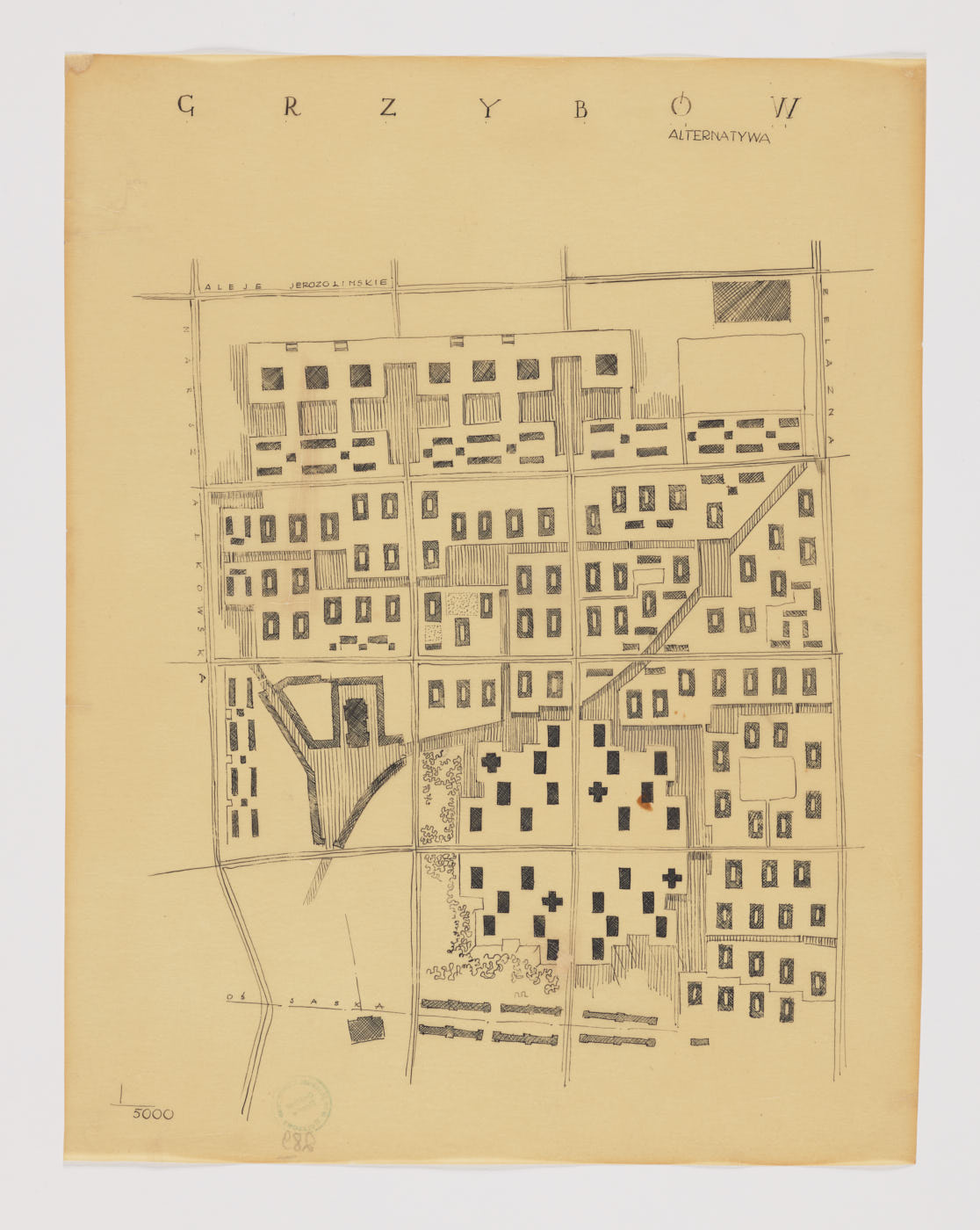

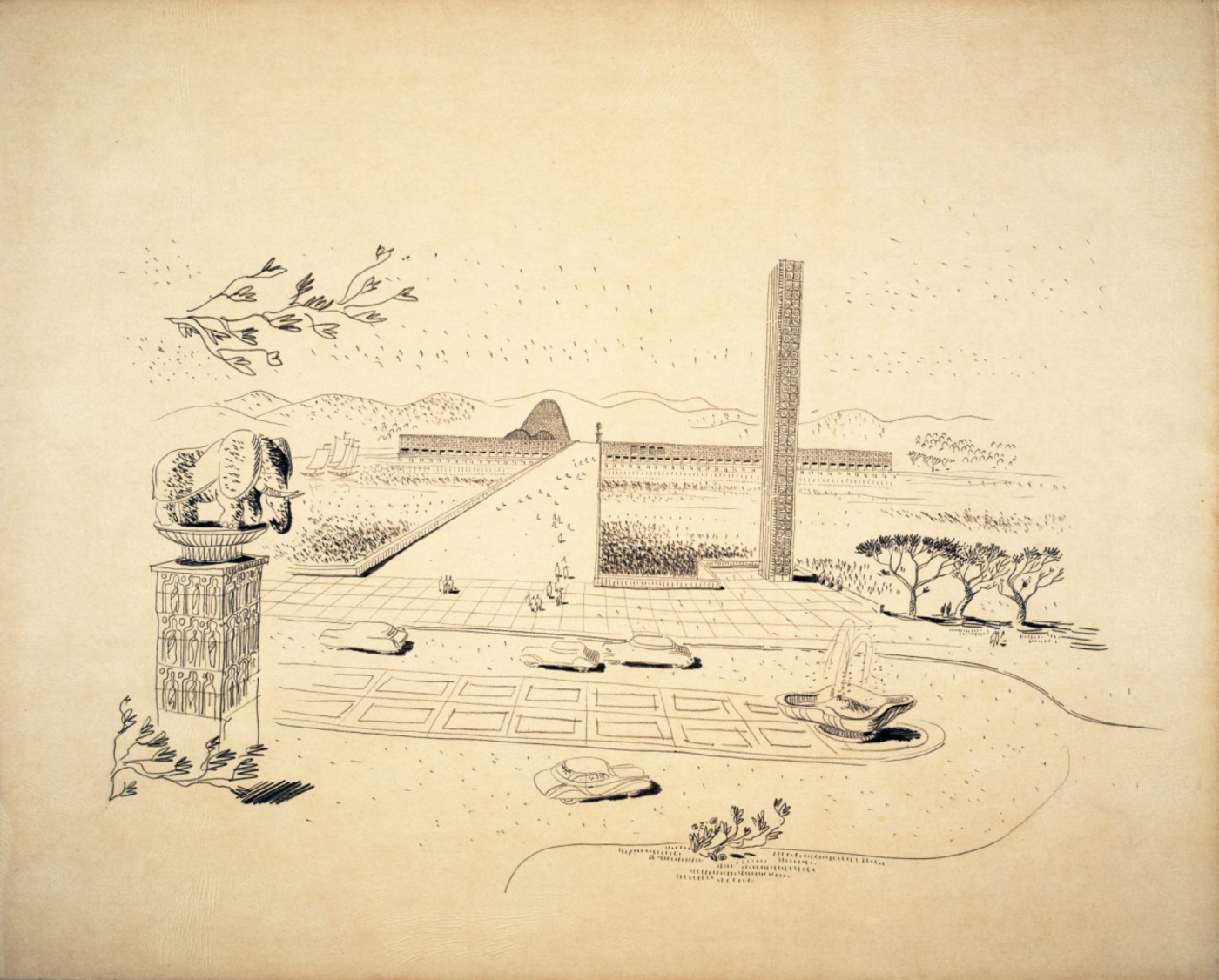

The first attempts to plan the post-war reconstruction of Warsaw began under the German occupation. Students and teachers at the underground school of architecture were conscious of the necessity of future reconstruction. Immediately after the war, Maciej Nowicki, was appointed the main planner of the central part of Warsaw.

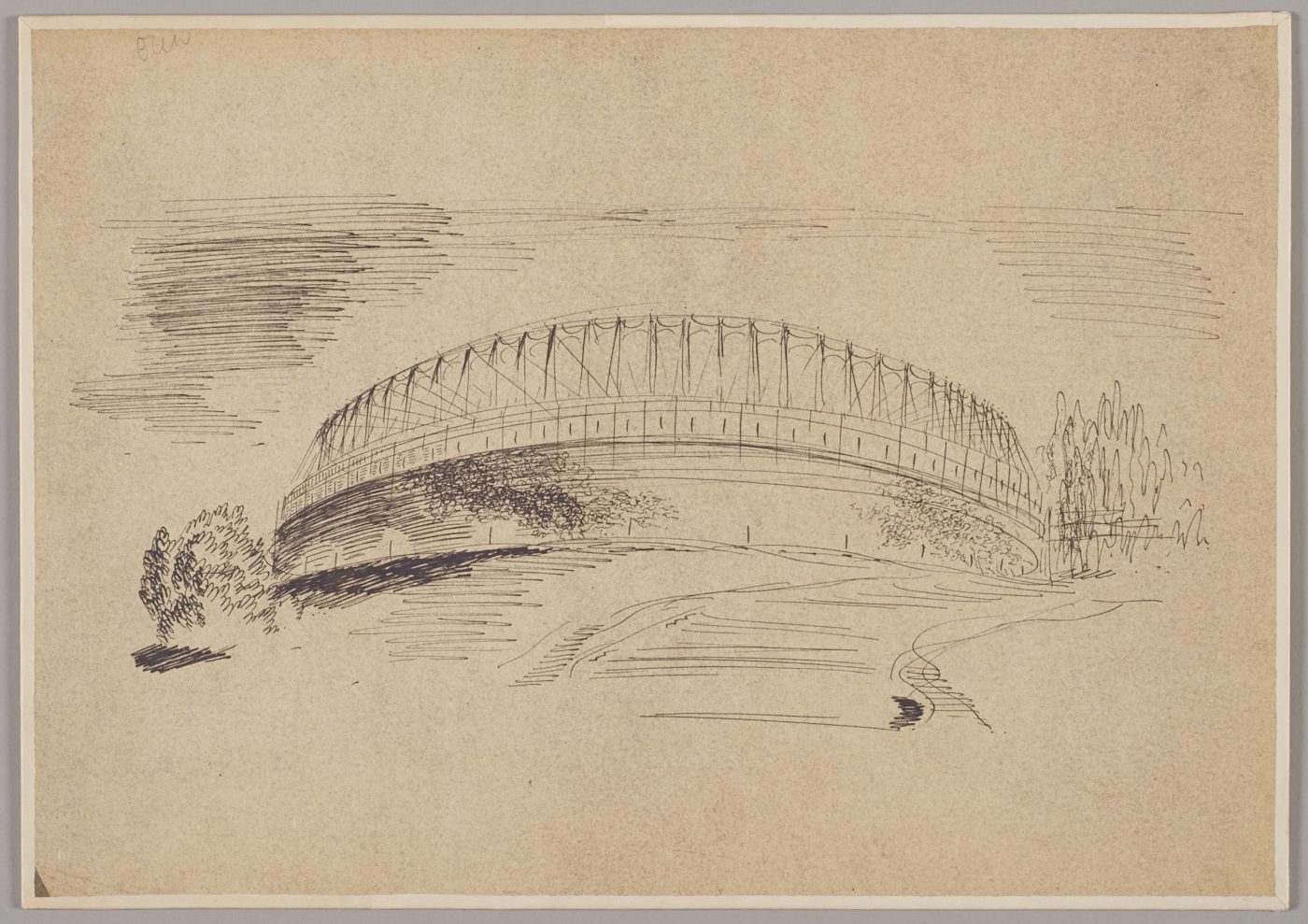

Part of Nowicki’s proposal for the city center was a new parliament building. It was monumental in its round shape and experimental in its construction, with a roof suspended from steel cables.

The business district, planned on the site of the former Warsaw Ghetto in the Grzybów district, presented a design challenge due to the overwhelming destruction and rubble. Instead of removing the rubble, Nowicki decided to incorporate it into his design to differentiate the streetscape. To maintain the human scale of the complex, the maximum height of the commercial buildings was set at four stories. He planned to use prefabricated structural elements to facilitate a quick construction process.

Perhaps the life of no other architect so well reveals the dilemmas and choices that have presented themselves to the modern architect; or so sensitively indicates the direction that a more humane culture must take, if it is to save itself from the sterility and dehumanization that now threatens our civilization.

Lewis Mumford

United Nations Headquarters in New York

In late 1945, Nowicki went to the United States as a cultural advisor to the Polish diplomatic mission and later participated as a Polish consultant in the Board of Design’s work on the new UN Headquarters. He became part of the working group headed by Wallace Harrison, which included notable figures such as Le Corbusier and Oscar Niemeyer.

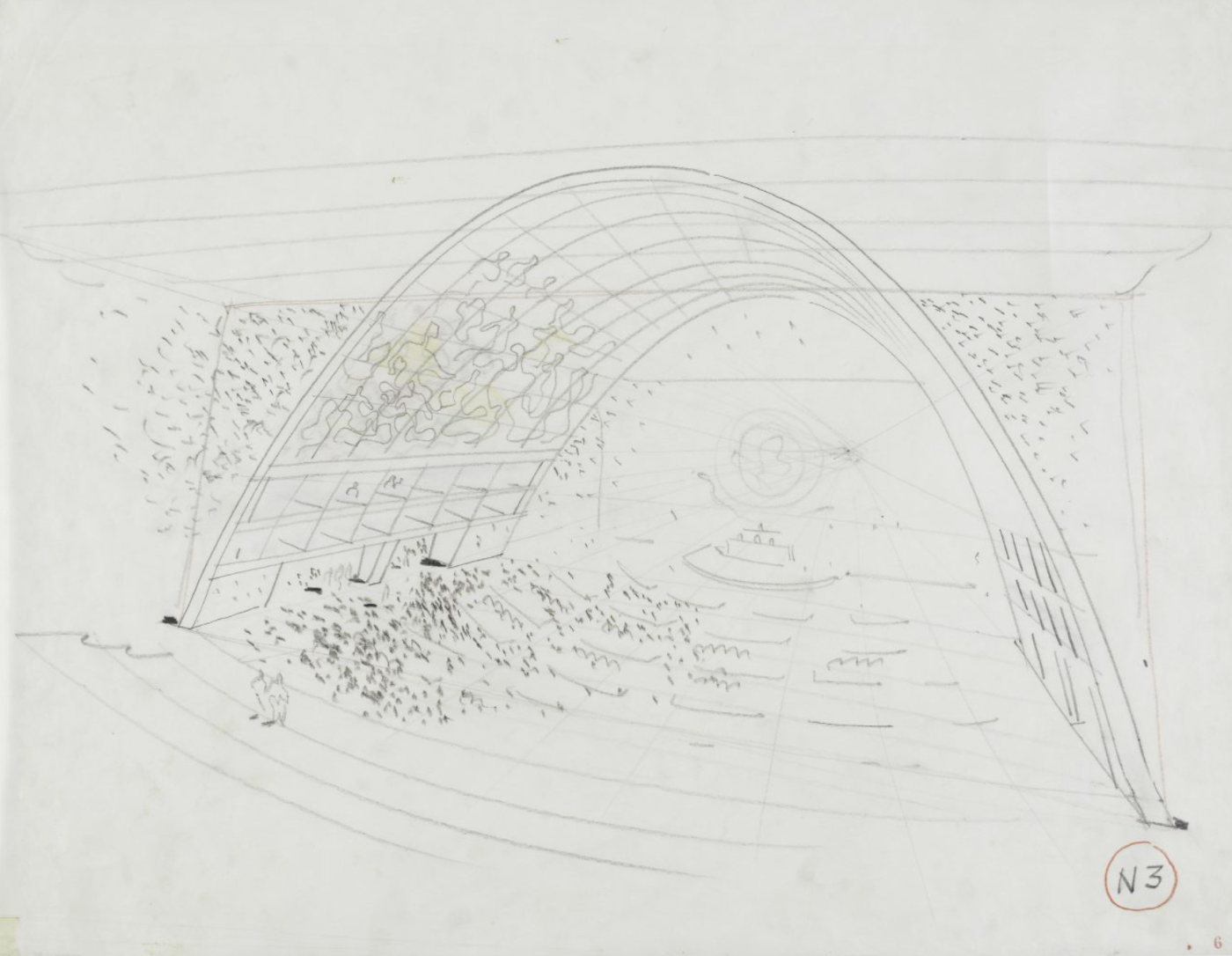

In the case of the UN he believed that the design of its headquarters was a means of defining the identity of the organization. Nowicki saw here not only a cluster of buildings, but also a physical manifestation of the united postwar world. He was the author of five concepts; only two of which have survived to the present day.

North Carolina State Fairgrounds

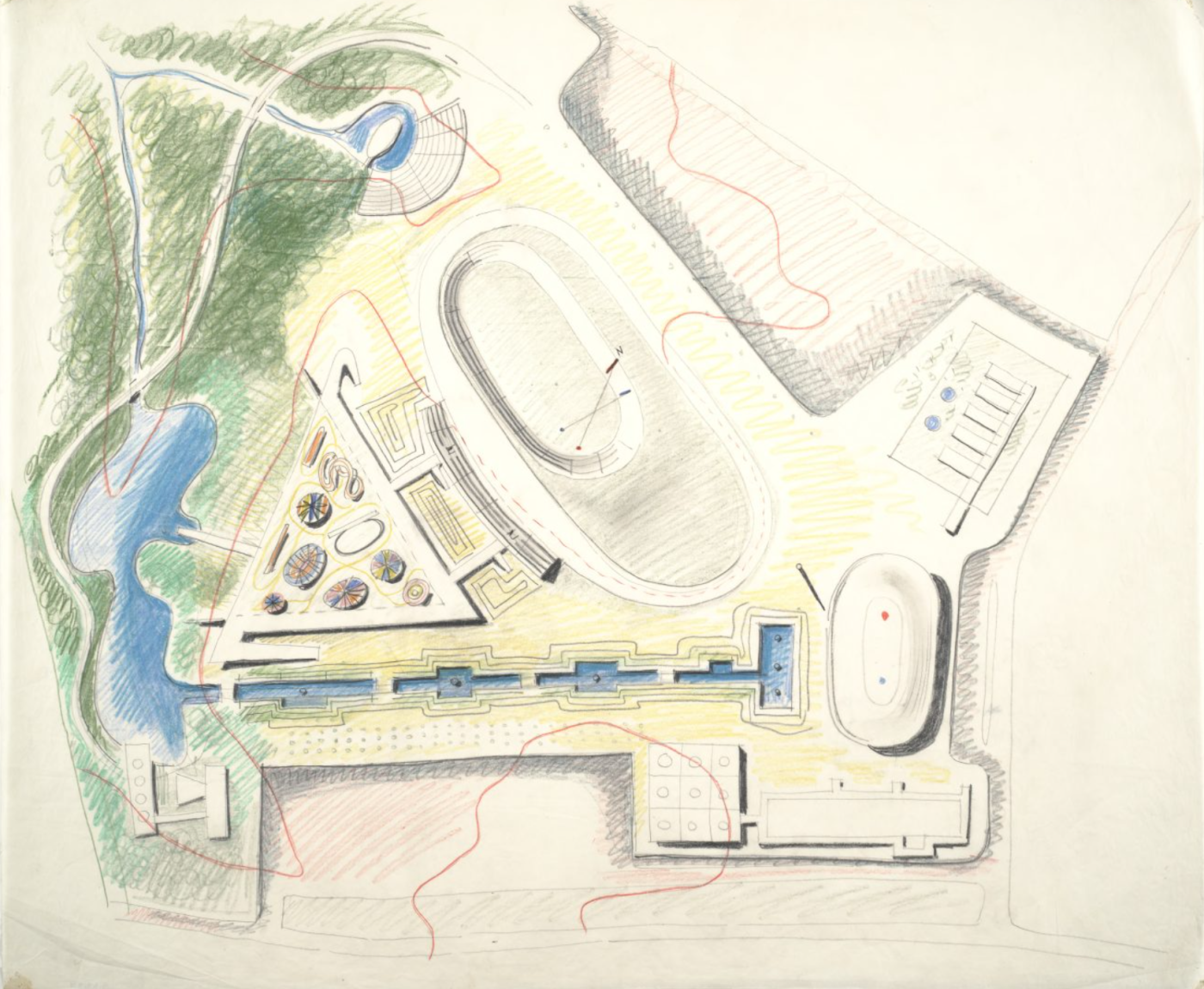

Thanks to his collaboration with William Henley Deitrick, Nowicki was able to participate in a wide range of design activities in Raleigh. Beginning in January 1950, they worked on designs for the North Carolina State Fairgrounds. Nowicki and Deitrick held numerous meetings with Fairgrounds officials, whose intent was to promote North Carolina as a progressive state. After a series of designs had been brought to completion only with great difficulty, Nowicki was commissioned for a project that would finally allow him express his architectural vision.

Dorton Arena in Raleigh, NC

The Paraboleum (now Dorton Arena) was designed for the prosaic function of exhibiting farm animals. Its structure is based on two parabolic arches made of reinforced concrete, inclined in opposite directions. The roof is suspended from steel cables stretched between them above a huge one-room hall.

The key to this innovation is the complete departure from the classic system of post and lintel structure. The roof seems to float above the fully glazed exterior walls, which no longer have a load-bearing function.

Completed in 1953, the arena received an award from the American Institute of Architects and was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1972 for its architectural significance.

Chandigarh, India

Nowicki’s last major commission was the design of Chandigarh – a new capital of the northern Indian state of Punjab, on which he worked with Albert Mayer and Julian Whittleys..

The city was laid out on a plan that resembled a leaf. The main commercial axis was connected to the government building complex by a highway, from which smaller roads branched off on each side. The plan unified the city while creating small, intimate residential areas. The clear hierarchy of the street system provided easy connections from the residential neighborhoods to the commercial axis and to public facilities such as the Capitol, the lake, the public forum, and a large hilltop park. The Indian authorities, intrigued by Nowicki’s designs and methodology, offered him a ministerial post to oversee the construction of Chandigarh. Before the project could get underway, however, Nowicki had to return to Raleigh and died in a plane crash on his way home.

The sudden death of Nowicki ended the possibilities for further refining the Mayer plan to define a modern urbanism rooted in India’s tradition.

Tridib Banerjee PhD, Professor and James Irvine Chair of Urban and Regional Planning at the School of Policy, Planning and Development, University of Southern California

Colophon

Organized by: National Institute of Architecture and Urban Planning

Co-organized by: Permanent Mission of the Republic of Poland to the United Nations in New York, Under the patronage of Krzysztof Szczerski, Permanent Representative of the Republic of Poland to the United Nations in New York

Collaborative input: Consulate General of the Republic of Poland in New York

Programming partner: Polish Cultural Institute New York

Scientific curator: prof. Bolesław Stelmach Ph. D. Arch.

Curator: Kacper Kępiński

Exhibition architecture: Only If Architecture (Karolina Częczek)

Visual identity: Katarzyna Nestorowicz

Editing: Urszula Drabińska

Translations: Natalia Raczkowska

Acknowledgments: Peter Nowicki, Dominika Stecyk, Izabela Gola, Agata Lupoměská, Izabela Iwanicka-Dzierżawska, Piotr Kibort, Ewa Perlińska-Kobierzyńska

Co-financed by the Polish Ministry of Culture and National Heritage.