Polyperiphery. Public spaces after ‘89 and ‘22

Semi-peripheral location and historical context of Warsaw, Brno, Bucharest and Kyiv have created the situation where the shape of common space is subject of constant change, never reaching its target form.

Development of the major Central and Eastern European cities is based on the need of dynamic adaptation, often ahead of the long-term strategic planning. Following the problematics of polycentricity, ownership and collaboration and rebuilding, the exhibition presents the documentation of the site visits, interviews with local experts, spatial data and summary of planning documents. Various perspectives including municipal administration, NGOs, researchers and inhabitants depict the diverse context of the four cities. Comparison of four locations gives an opportunity to confront the similarities and different trajectories in coping with the common space struggles and housing policies in the region after 1989.

The exhibition has been already shown in Kyiv and Warsaw during autumn 2021 under the name „Poliperiphery: spaces of negotiation”. The 24th of February 2022 has completely changed our reality. The main architectural task after the russian invasion, will be the reconstruction of Ukrainian cities, including provision of fair housing and renewal of public spaces. As an appendix to the exhibition, we asked Ukrainian architects, academics, activists and investors about the current initiatives and the challenges of the post-22’ rebuilding.

Kyiv – Governance (autumn 2021)

Comfort Town

The colorful, internally coherent Comfort Town estate is an island of civilization and good management in a sea of mediocrity. At least that is how it is perceived by its residents, which is confirmed by numerous studies and academic articles. The investor of the development adopts a similar narrative, emphasizing its qualities in comparison to the neighboring older buildings and other development projects in Kyiv. The uniqueness of the estate is emphasized by the fence surrounding the entire complex, which was not initially planned by the designers from Archimatika office. This fence creates barriers and highlights the inequalities that are growing due to the economic crisis, among other things. Comfort Town is presented as an ideal place to live. Its residents, however, often have to make use of the public infrastructure of the older housing estates around them without offering their neighbors access to the one located within their gated complex.

Archimatika is currently working on a concept of the model prefabricated affordable housing structures which would facilitate fast construction and qualitative shelter for the internally displaced victims of Russian invasion.

Poznyaki-2

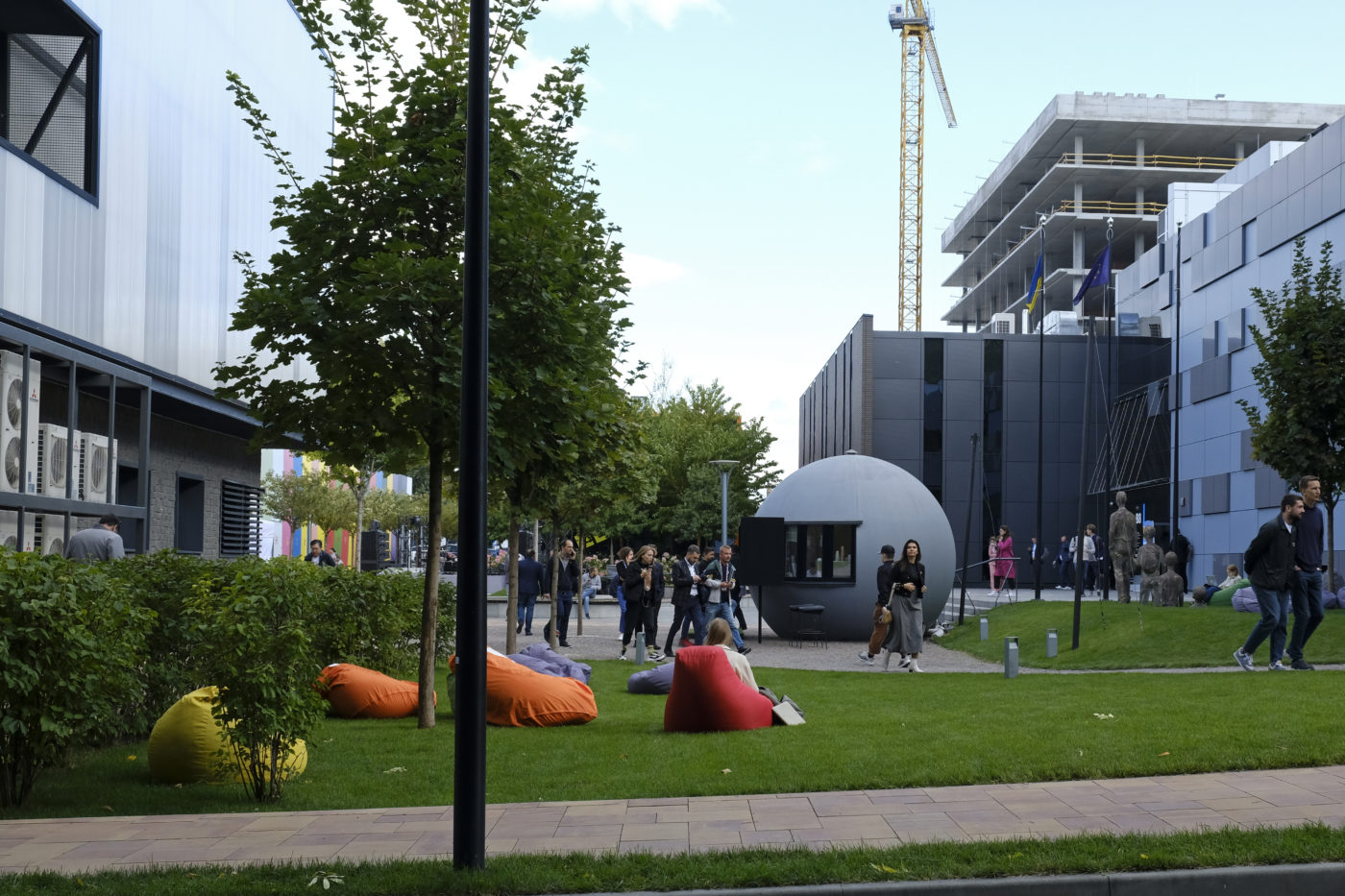

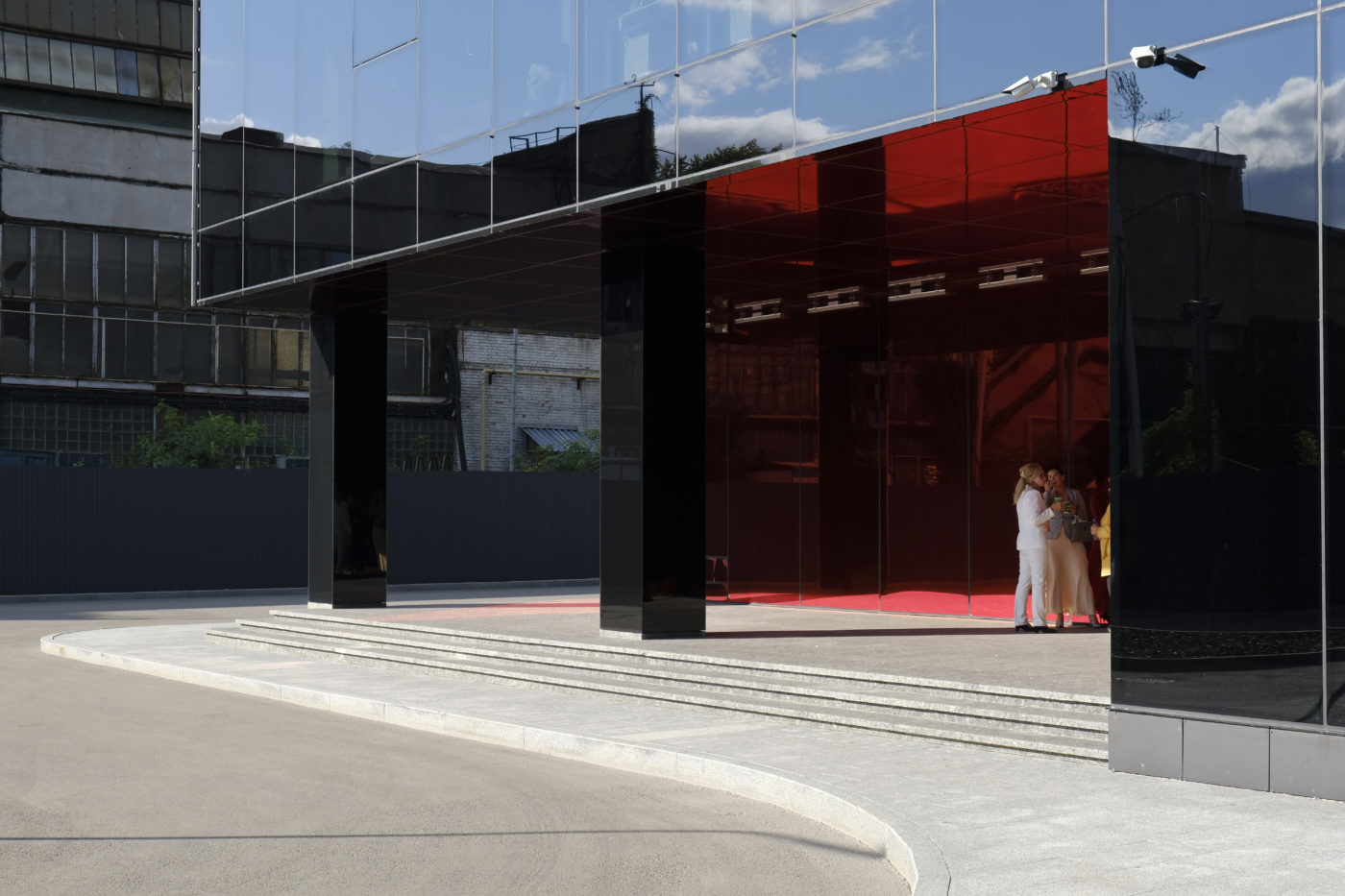

UNIT.City

Sofiivska Borschahivka

Ukraine – Rebuilding

The initial name of the exhibition shown in Kyiv and Warsaw in autumn 2021 was „Poliperiphery: spaces of negotiation”. The Russian invasion of Ukraine brought a new, dramatic context and meaning to the topic of space and territory negotiation which should never happen. Ukrainians on their way to victory do not negotiate with the aggressor but focus on the current defence and future rebuilding of their destroyed cities. While wartime is a difficult condition for any long-term strategies as the situation changes almost every day, the architectural and activist community of Ukraine try to be flexible and dynamically react to the challenges with their numerous initiatives. Rebuilding does not only concern the material structures but also community straightening and improvement of systems and laws. As the repair process concerns many regions of Ukraine, we decided to show the wider context of the whole country instead of one city of Kyiv.

Oleksandr Anisimov: Housing policy from ‘91 to ‘22 and after

The privatisation of the 1990s resulted in the current situation of the Ukrainian housing market where practically all the stock is privately owned, lacking municipal nor governmental offer. Commercial and private entities create the market rules, dictating prices, location and construction quality of the houses. Immense scale of housing and infrastructure deterioration has been caused also by the mismanagement due unclear ownership status of the building and plots, together with lack of sufficient funds. Rapidly rising prices of apartments, even still after the 2008 financial crisis and 2014 war, excluded many people from the rental and purchase market while increasing energy costs make it often impossible to cover the basic costs of living and brought the threat of energy poverty.

The wartime context is very difficult to take a long term view to analyse and resolve the problems of housing with wider, effective strategies as the circumstances change dynamically almost every day. The massive displacement of eastern Ukraine inhabitants to western regions of the country will definitely require broader policy but first, thorough administrative work needs to be done to map the scale and direction of migration of people who didn’t deregister from the cities they fled. Moreover, international financial aid for municipalities will be required to successfully rebuild war-affected regions, not only in terms of building reconstruction but also the infrastructure, economy and the whole housing system. Currently, these are the private developers who might be responsible for the country rebuilding and potentially also make business on this condition. We need more public involvement in the provision of housing. Ad hoc initiatives to provide emergency shelter and social housing to those in need are already taking place, however more systematic solutions will be required. I am engaged in a research-centred initiative with the aim to provide high-quality analysis of the current conditions and of the experience and policies of housing reconstruction after the war and policy advising guidelines for municipalities and the state.

– Excerpt from the conversation with Oleksandr Anisimov, Urban researcher, MSc Urban Studies, cofounder of the research initiative aimed to study and advocate change in urban policies NewHousingPolicy.com.ua, initiator of the research project on architecture and urban planning of 1980s in Ukrainian SSR and Eastern Block AfterSocialistModernism.com.

Spilnota – New Generation Developer

Interview with Igor Raikov, Chief Executive Officer (CEO) & Founder at Spilnota developer company and Founder at ULPM School of Professional Development:

- How would you imagine fair real estate in postwar Ukraine?

In my opinion, the real estate market will hardly change. However, the presence of a neighbor-aggressor will affect the construction and planning, including better equipped underground parking lots and bomb shelters. Most likely, the model of investing in a new apartment „in a pit” will fade from the market as buyers will prefer to purchase an already built facility instead of an uncertain long-term investment.

- What are your professional experiences from before the war?

I have three areas of work related to the real estate sector, including „Spilnota – Next Generation Developer”. Before the war, we created great concepts for housing estates, designed houses and attracted investment for their construction. We also have a company that designs master plans for settlements. Another field is the ULPM School of Professional Development, a business school where we teach developers and owners of construction companies from all over the country the best world practices in the implementation of projects in all real estate sectors.

- Which real estate market pathologies could amplify in the context of the country redevelopment?

First, I am against quick temporary solutions which cost a lot of money. We have examples of the transformation of modular towns into ghettos. Attempting to create new modular cities in the middle of nowhere seems artificial to me. We must provide decent conditions for the residents. The city is a complex system of social relations that has been formed for centuries.

Secondly, the return to permanent residence must be separated from the issue of rebuilding completely destroyed neighbourhoods and cities. Nobody should devote their life to waiting for the destroyed quarters to be rebuilt. It is also necessary to abandon the ideas of „resettle and provide” as this is a Soviet approach. Man needs choice and freedom so compensation decisions are urgent.

Third, quick methods of erecting typical buildings to rebuild as quickly as possible are not the best solution. European methods of rapid construction require re-equipment of the technological lines, and most importantly – experience in the construction and operation of such buildings as the main experience we have in the operation of Soviet panels.

- How does your company contribute to the reconstruction initiatives or other forms of support/solidarity?

On the basis of the school, we established a volunteer initiative to rebuild destroyed apartments for those who lost them, involving everyone who could help: designers, builders and fundraising resources – materials and money. We aim to meet the needs of 10 families. An apartment building in Obolon, which was destroyed by a missile strike, was also taken into custody. We cover the costs ourselves to study the destroyed structures of the building and design new ones, so that in summer the city administration can start the reconstruction of the building, and in winter people will be able to enter their homes.

CO-HATY – inhabiting vacant spaces

https://www.metalab.space/co-haty-eng

Project by Metalab, Urban Curators and Krytychne Myslennia

Since the beginning of the Russian war against Ukraine, around 2,8 millions of Ukrainians migrated to the Western part of their country The city of Ivano-Frankivsk officially registered over 40k internally displaced persons (IDP) which means its population growth of at least 20%. CO-HATY is a program providing long-term housing for internal migrants. The project started with a transformation of the abandoned dormitory in Ivano-Frankivsk, initiated by a group of professors from National Technical University of Oil and Gas, joined by the urban laboratory of Metalab (Ivano-Frankivsk), Urban Curators (Kyiv), and Krytychne Myslennia (Kharkiv) – a group of activists with urban and architectural expertise. The team has been working together with the future residents on the renovation and arrangement of the building. In addition to private spaces, the refurbished dormitory will feature cоmmon functions such as a canteen, kids room or workspace. Important part of the process is to create a community. The team states that such an approach of adaptation of existing structures fills the typology gap between the insufficient ad hoc emergency shelters and the big scale housing complexes development that require more time.

HATA – in Ukrainian Hut/house

COHATY – in Ukrainian „TO LOVE”

co-HATY is a co-housing project for people who lost it in the time of war

Urbanyna – public spaces guidelines

Urbanyna is a team of urbanists, architects, and designers from Kyiv. Since 2020, they launched urban design courses for activists and created a non-profit office for urban projects. Urbanyna research and collect data about urban territories, design public spaces, create street objects, organize annual festival. Just before the current war, they published „Handbook of park improvement” (PDF available online) – an accessible manual with illustrated guidelines for design of green public spaces. The graphic material includes referential pictures, 3D models, and dimensioned drawings, making the book a compendium of knowledge for designers, planners, investors and decision-makers. Recently, the group started work on a guide in a similar concept but focused on the Ukrainian cities rebuilding after Russian invasion. The book will describe in detail the complex solutions for modern streets, the rules of their lighting, landscaping, infrastructure, playgrounds, street signs and even balconies.

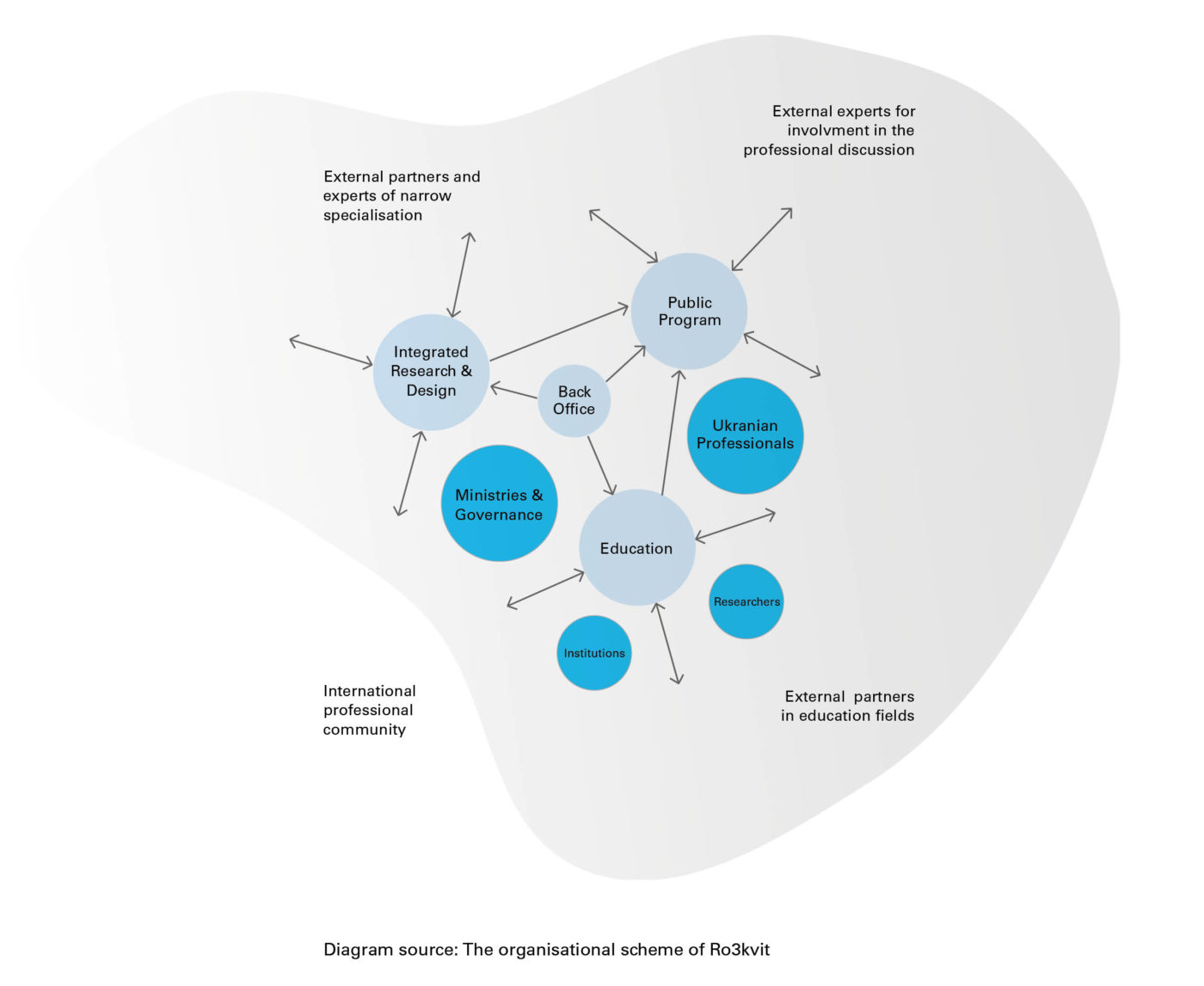

RO3KVIT – Urban Coalition for Ukraine

The coalition of the architectural community has been recently formed in Ukraine. Excerpt from the Ro3kvit presentation booklet:

Mission:

We will develop a methodology for rebuilding Ukraine’s physical infrastructure and cities. A new way of looking at urban design, co-creative organisation and sustainable development.

We work at different time speeds: from urgent needs now, towards a sustainable future. As the researchers on post war country rebuilding in our team, we say: ‘we need to be ready when peace comes’.

We are a coalition of Ukrainian and international experts (who have been working in the Ukrainian context). We work in urban planning, regional planning, housing and related topics as economy, legal issues and policy making.

We provide a lively platform, to connect and activate all expert teams and initiatives on different levels in Ukrainian and international society, in an open network structure. This platform will result in a guideline, a roadmap and an inspiration book for rebuilding post war cities in Ukraine. We will develop pilot cases for several cities.

What is a post war Ukrainian situation, and what is unique for a certain region or city? There will be a constant interaction between abstract and specific design and between public debate and scientific research.

Kharkiv School of Architecture – Rebuilding the University

The text based on the KhSA official statement and the interview with Oleg Drozdov, leading Ukrainian architect (Drozdov&Partners) and co-founder of the Kharkiv School of Architecture and the school’s deputy vice-chancellor Iryna Matsevko published on dezeen.com

Founded in 2017 in Kharkiv, the School served as a communication platform for the Ukrainian and the international architectural communities, promoting an exchange of the latest knowledge and new ideas. Together with renowned experts, the team of the School designs and launches unique educational programmes, which are innovative both for Ukraine and the whole world. However, the war has forced Drozdov and Matsevko to rethink the direction and role of the institution.

Now Kharkiv Architecture School wants to make a strong statement and stay in Ukraine.

With no prospect of immediately returning to Kharkiv, Matsevko and Drozdov are working to establish a semi-permanent base for the Kharkiv School of Architecture in Lviv. The school is now reformatting its program, and they are resuming online learning.

A group of around 15 staff and students are now located in Lviv, with the rest of the school’s 40 students and 25 faculty expected to join over the next two months. Plans for the Kharkiv School of Architecture are still in flux and its staff aim to remain in Lviv for at least a couple of years.

The school will aim to educate students on a practical level to understand how the country and city of Kharkiv in particular can be rebuilt after the war. Along with teaching, the school is collaborating with students and Drozdov’s architecture studio to create spaces for others arriving in Lviv after fleeing from other parts of Ukraine. They have converted a sports hall in Lviv Regional Sports School for Children and Youth in Stryi Park into temporary accommodation for 132 people.

For these purposes they used the Shigeru Ban’s Paper Partition System (PPS) which is based on using paper tubes as structural frames and cloths to be hung on to the frames.

Warsaw – Polycentricity

Extreme growth and development were the main ambitions of the early 21st century Warsaw urban policy. Investment-oriented approach led to the intense execution of residential complexes on the plots, scattered around the city, referred to as “development areas”. The 2006 Study of conditions and directions for spatial development (referred to as the Study) assumed a dynamic population growth of Warsaw – up to 3.5 million inhabitants. Investors’ encouragement and preferential conditions for construction, together with the demographic projection resulted in the urban sprawl of the mono-cultural residential areas.

The population did not increase as rapidly as the city officials anticipated. The policy of growth has contributed to the fast city development, but not in a well-controlled and sustainable manner. The provision of the means as social infrastructure, public transportation and good quality public spaces did not keep pace with the fast construction executed by the private sector. One of the main goals of the new Study, which is currently being prepared by the Urban Planning and Development Strategy Studio of the City of Warsaw, is the repair and improvement of the polycentric urban network, taking into account i.e. biodiversity (blue-green infrastructure), mobility and social conditions. Warsaw is a city with a historical structure based on the scattered and diverse areas of higher density. Many of them naturally developed their local centers. Still, some of the neighborhoods, especially those built over the last 30 years, are urgently in need of public spaces where the social life, services and commerce would concentrate.

As a strategic policy document, the new Study, seeks to determine these potential areas. The complex, multi-step Polish planning system and a certain autonomy of the districts does not make the implementation of the local centers easy. While only 39% of Warsaw’s area is covered by Local Zoning Plans (MPZP), building permits in other areas are issued through an ambiguous path of a Decision on development conditions (commonly referred to as W-Z). In the face of the flawed planning framework, the search for the alternative, locally-rooted tools, and residents’ involvement could contribute to the creation of the new public spaces. Local centers often spontaneously occur in different areas than those defined by the official planning documents.

Rondo Wiatraczna

Serving both as one of the local centers of Grochów (part of Praga-Południe district) and the supra-local transportation hub of the entire right-bank Warsaw, Rondo Wiatraczna is perceived as chaotic and problematic. Typically for the post-’89 spaces of Central-Eastern European cities, the area is in limbo, constantly waiting for its “final transformation” which may never be achieved. Two big infrastructural investments are planned – a car tunnel in the axis of Aleja Stanów Zjednoczonych and Ulica Wiatraczna, connected with the expected construction of a metro station. Dependency on the anticipated underground processes postpones what could be improved on the eye level – potential remodeling of Rondo Wiatraczna into a legitimate urban square. Transformations that have already happened apply to the urban fabric of buildings: the iconic modernist department store “Uniwersam Grochów” run by the “Społem” cooperative was demolished in 2016, giving up space for the ultra-dense high-rise hybrid of the developer housing and shopping mall, which could serve as a landmark of the neoliberal direction in Warsaw’s growth. The “Społem” grocery store remains a part of the mall, however surrounded by the generic, international chains. At the same time, the area of the roundabout fortunately has not been dominated by a single commercial entity, and it still provides a multitude of diverse services, including traditional shops, pavilions and a well-functioning marketplace, eagerly visited by the locals. Large corporations replacing smaller players and spatial domination of the transportation are not the only threats for the area. Polish cities are afflicted by the so-called “betonoza” (“concretosis”) phenomenon. Vast public spaces covered with concrete and paving become unbearable in hot weather and in view of climate change, should be remodelled into more friendly, green areas.

Ursus Niedźwiadek

Niedźwiadek is the largest housing estate built in the 1970s by the Workers’ Housing Cooperative “Ursus” for the employees of the neighboring tractor company. Ursus, as many other industrial plants in Poland, struggled with difficulties related to the restructuring and privatization during the political and economic transformation period, until its final decommission in 2011. The shutdown of the local industry has freed up a significant number of plots for new development. It resulted in a dynamic, ongoing construction of the new, big scale residential complexes built by private sector investors (i.e. Ursa Sky, Ursus Nova, Ursus Centralny etc.) With the increasing population and housing density, the area was missing a high quality public space for its current and new residents.

The public space development in Ursus was completed by the city and district municipality in early 2021, as one of the locations of the Warsaw Local Centers pilot program, carried out together with the Association of Polish Architects (SARP).

Both functional and spatial characteristics, as well as the process of their implementation, allow to classify the Ursus-Niedźwiadek Local Center as a model realization of the program premise. The location has been selected in an existing place with a high communal potential, close to commercial pavilions, the church and the swimming pool. The local center remodeling includes playground modernization, construction of a sports field complex, park greenery and landscape. Inhabitants took an active part in the participatory process of public consultations.

Wolumen

Chaotic dynamics of the bazaars, marketplaces and flea markets is the best catalyst for social interaction. This unpredictability and certain non-framing seems to scare some of the officials and planners, often seeking to sort them out and clean them up, which often leads to the loss of their authentic character. This happened in the modernized Bazar Różyckiego in Warsaw’s Praga-Północ district where the new, systematized pavilions have been installed. This will probably happen in the centrally located Hala Mirowska where the public-private partnership revitalization tender has recently been announced. And it has almost happened on Wolumen – the biggest marketplace of the Bielany district. The team of architects and planners preparing the local zoning plan project proposed approving a high-rise office and residential development on the bazaar site, while maintaining the marketplace function on the ground floor. The proposal has been widely protested by the residents and the estate council. The “We are not giving up Wolumen” petition gathered 4600 signatures and the local center with a 40-year history did not change its original form and function.

Ursynów

The structure of the vast district composed of numerous residential estates evolved over the years, starting with the mass panel housing in the 1970s. The metro line construction, started in 1985, had an enormous impact on Ursynów’s development in the late 80s and early 90s, when it opened. Postmodern architecture has impetuously stepped in the never-completed modernist development with its foreign fabric, typology and urban layout.

Marek Budzyński, architect and author of the large part of the district, also designed the iconic Church of Ascension. It is a particular situation where the local center has been situated around a temple – on the one hand, a kind of symbolic violence, and on the other, a reference to the Polish tradition. Its monumental facade dominates the square in the form of a traditional old town market where the public life and commercial functions occur, continued in the shopping passage. Spatial separation from the main traffic arteries, its compact form and orientation towards the residential area give the place an intimate character, fostering social interaction. The square smoothly transforms into a park, creating a square-park which can be considered a characteristic feature of Warsaw typology.

Mokotów

In 2016, the municipality together with SARP (Polish Architects Association) organized an architecture and urban planning competition for the pilot local center in the “Orszy” green square. The implementation of the winning concept is currently suspended while the works on the local zoning plan for this part of the district and public consultations continue.

Mokotów is an example of a district where the numerous, spontaneous local centers catch on and flourish around the cultural and commercial functions popular among the residents and visitors. One of them is the square in front of Nowy Teatr – the public cultural institution located on the former premises of the municipal sanitation department. The empty post-industrial concrete square is not a place one would first think of as a friendly public space. However, despite the unwelcoming impression it may give, it became an important meeting point and the concrete is gradually being replaced by more greenery. The democratization of the gastronomic and cultural offer could give the place more of a public character, as currently it is aimed at more privileged social groups, contributing to the gentrification of the area.

Francuska

Iconic, modernist facades of the 1930s villas, townhouse frontages and green belts of trees stretch along Francuska – the main shopping street of Saska Kępa. The linear local center intersects the green, mostly low-rise neighborhood, resembling an idyllic resort promenade, including cafes, restaurants and colorful umbrellas suspended over the street – the universal symbol of the generic gentrification attempts. What distinguishes this street from a holiday resort is the prevalence of vehicular traffic – cars, public buses and parking spaces along the sidewalks. The municipality has recently carried out an “ecologic facelift” of Francuska, introducing biodiverse rain gardens instead the parking spaces. Unfortunately, drivers did not respect the new arrangement and completely destroyed the plants and basins by parking on them.

The excessive amount of cars and frequent traffic obstructions in the area are related to the National Stadium commissioned for Euro 2012 – football supporters and mass events attendees make daily life difficult for the residents of Saska Kępa.

Brno – Ownership

Besides the dramatic affordable housing shortage, social housing is not the main ambition of the Brno municipality agenda or at least not the most fulfilled one. As per the Draft Concept of Social Housing in Brno 2020-2030, the city of Brno operated only 227 social flats in 2019 which represented only 0,8% of the total number of units owned by the city and a marginal fraction of the total housing stock. The most affected by the situation are the unprivileged groups of residents like the socially excluded Roma community. The brutal market dominated by profit-driven developers and private landlords forces them to the overpriced rental at the poor conditions private dormitories which they can not afford, being often pushed into homelessness crisis.

The documentary by Tomáš Hlaváček “Bydlet proti všem” (“Housing against everyone”) takes a look at the civic and political struggle for a new approach towards homelessness and the right to housing for the poorest. The “Rapid Re-housing” project (internationally known as “Housing First”) was initiated by the Žít Brno political party of the activist background and led to the provision of 50 apartments units to the poorest, together with the social workers support. The programme won several awards for social innovation across Europe, including the SozialMarie 2018 prize in Vienna. However, it ran in Brno only for two years (2016-2018). The city council under the Mayor Marketa Vankova (ODS – right-wing conservative party) decided not to continue the project which was covered in 95% by European Union structural funds and only 1.6% by the municipality.

In the city dominated by the market laws, some successful social and affordable housing initiatives occur. However, one-off realizations of the council projects and numerous policy papers are a drop in the ocean. Brno is in urgent need to redefine the new housing models to break the monoculture of ownership. A return to the lost housing cooperatives traditions could be a solution, but can be hard to carry out with a completely privatized housing stock.

Lesná

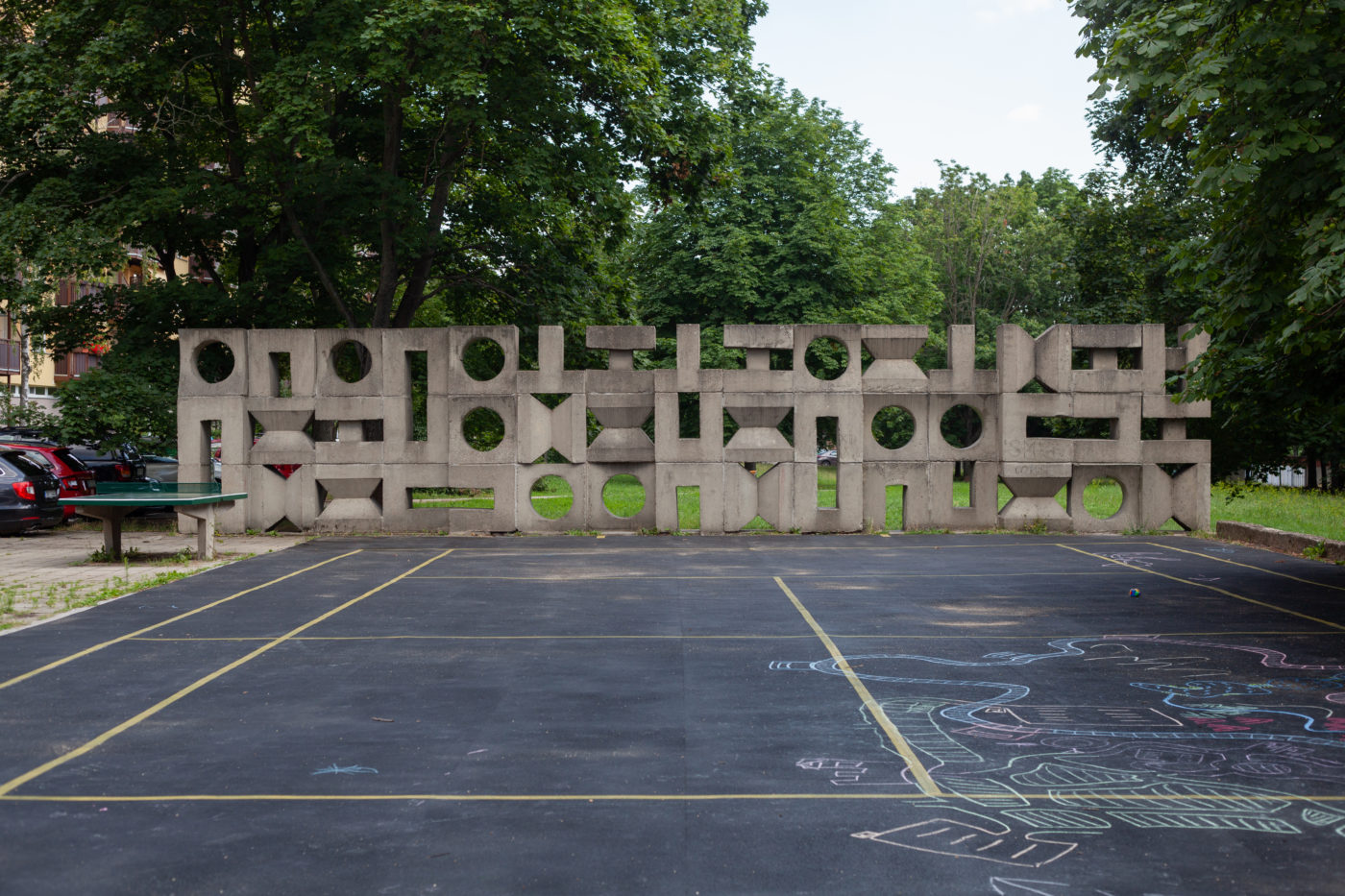

The picturesque modernist prefabricated panel housing estate overlooks the city. Situated on a former military plot on the northern outskirts of Brno, on a hill in the middle of the forest, constructed in 1962-70 and designed by František Zounek and Viktor Rudiš, garden city Lesná was the largest investment of the time in post-war Czechoslovakia. The big-scale residential blocks were developed together with a broad functional and social infrastructure, including shopping pavilions, artistic urban sculptures, playgrounds, schools, a healthcare center and the TESLA Sports and Swimming Center which finished a while later, which is not the only iconic public building of the area. In 2020, architect Marek Jan Štěpán completed his life-long project, initiated 30 years ago – the Church of Beatified Restituta. The interior of the building illuminated with the rainbow colors was all over the design websites recently, surprising that in the mostly atheistic Czech Republic, a contemporary building of a Catholic church would be the community center of a neighborhood.

The vast area of the whole Lesná with its well-maintained greenery and public spaces is located on the property of the city of Brno that maintains it. The residential buildings were developed in the 60s, and later operated mostly by the housing cooperatives (stavební bytové družstva), and partly by the state.

After 1989, together with the newly adopted acts of 1992 and 1994, the process of privatization of the apartments started. As almost no building of the area was listed in the land register at the time, they all had to be surveyed, to be later divided into individual units, which could be transferred to private ownership of the members of the cooperative. Difficult times for housing cooperatives in Czechia began. To illustrate this transformation: today less than 30 units out of 7,100 remain in possession of the biggest South Moravian housing cooperative Nový Domov.

Kocianká

Not far from the model Czechoslovakian panel housing estate of Lesná, the ongoing Panorama Kociánka development emerges from the concept of Arch.Design architecture studio and Unistav Development company. Mostly low-rise, yet dense development is situated on former allotment gardens and green urban wastelands, providing residents with distant views of the Brno skyline. What happens up close, at the eye level, could be defined as today’s sorrows of Central and Eastern European housing estates in a nutshell. The private developer does not invest in social infrastructure because in view of high demand for housing in the city, the apartments will sell anyway (Panorama I, II, III phase – already sold). While the complex of neo-modernist housing blocks, urban villas and row houses respects the guidelines of the Urban Development Plan, its landscaping seems to ignore its biodiverse close surroundings of the forest and wild greenery. The concrete and paving makes it difficult to stand the hot weather. The maze of the redundant fencing makes the use of public space oppressive and incomprehensible in terms of the ownership status of the individual scraps of land.

Vojtova

Still lacking effective system solutions, Jiří Oliva, the Deputy Mayor for Housing manages to make some attempts to change the dramatic situation of housing affordability. One of them is the newly finished apartment complex on Vojtova street – two buildings of 116 social housing units – one of the largest residential development in the city in the last ten years.

The apartments have been offered to young couples and families as a first home on favorable terms. The rest of the 86 units serves as a nursing home for the elderly and persons with disabilities. The architecture of the development is appealing, with the buildings’ patio, facade galleries, sport facilities and emerging greenery.

The rental price per square meter of 62 korunas (2.50 euro) makes living in Vojtova very affordable compared to the rapidly increasing market prices in Brno – currently 274 crowns/m2 (11 euro/m2) for rental and 94 785 korunas/m2 in case of an apartment purchase (3 735,51 euro/m2). The gap between the rates of social and private market housing illustrates a burning issue of a big portion of inhabitants who earn too much to apply for council housing (representing a marginal part of the housing stock anyway), but not enough to buy or rent an apartment on the open market.

Nová Zbrojovka

Investment company CPI Property Group has taken on the ambitious task of transforming the former Zbrojovka premises into “a brand new lifestyle area” as stated on the project’s website. The weapons factory founded in 1918, was in bankruptcy from 2003 to its final decommission in 2007 and the following auction of the 20-hectare site for the amount of 707 million Czech crowns. Extensive, centrally located plots of the formerly prospering industrial plants are hitting record prices in many Central and Eastern European cities because of the high rate of return they bring to investors. The multifunctional project of Nova Zbrojovka, launched in 2016 is divided into stages, some of which have already been completed, including ZET.office building – “unique loft offices with industrial atmosphere – a space for companies aspiring a distinctive place”. The seemingly provisional arrangement of the public space, typical for the real estate projects which gentrify post-industrial brownfields, refers to the aesthetics of informal and grassroot initiatives. The demolition of the historical fabric continues, while the developer assures to maintain the most valuable buildings. The promise of the lively area including private high-end housing and services, raises concerns about the future social and spatial isolation of the vast space from the bordering districts of Cejl and Husovice.

Cejl

Cejl is a district of Brno inhabited by a largely socially excluded Roma population. Exclusion and stereotypes make it very difficult for the community to find proper housing. They are often forced to settle in state-subsidized dormitories with overpriced rent. The gentrification of Cejl began in the mid-1990s with the construction of the first real estate projects and new municipal institutions, such as the Museum of Roma Culture. The beginning of the 20th century brought the accelerated privatization of the municipal housing stock and the eviction of existing residents.

The construction of a social center in Hvězdička Park (designed by Zdeněk Sendler) is a part of the city’s revitalisation efforts. The building, designed by Radko Květo and Radek Sládeček, will serve for the social integration of the Roma community. The temporary building made of containers accomodates multi-purpose rooms for cultural activities, counseling rooms and offices for crime prevention assistants to support field social work.

At Francouzská 42, a dilapidated tenement house was rehabilitated by the City of Brno into 39 apartments for families or individuals with unstable housing conditions and low income (design by ateliér AGP). Social workers, social probation officers and employees of non-governmental non-profit organizations work with the tenants. They participate in resolving the tenants’ complex social situation and prepare them for the transition to standard municipal or commercial housing.

Kamenná kolonie

Kamenná kolonie (Stone colony) is a former workers’ settlement of around 130 little houses, informally initiated in a mined sandstone quarry in the 1920s. The complex has a pleasant, southern color scheme thanks to use of the reclaimed material coming from the brick factory and a specific slum-like structure because of the spontaneous development process of the dense row houses.

In the 60s, most of the working class inhabitants left the colony, being offered by the state the apartments in the newly built prefabricated panel blocks. Artists, bohemians and students began to move to Kamenna kolonie in the 1960s and 1970s, forming a new community. Today’s social structure of the neighbourhood is much more diverse, including the old residents and newcomers of many different lifestyles, backgrounds and motives – including investment. They all meet in the local bar and share the same problems: lack of sewers, poor accessibility to public transport and the most important struggle of the area: land ownership. Only a few owners of the local houses own the land their house stands on. Until the beginning of the 21st century the city was blocking its land purchase in Kamenná, imposing high, non-market prices.

Bucharest – Collaboration

Bucharest’s space resembles a patchwork of different orders, being a mixture of small-scale historical buildings and the traditional spatial layout, monumental avenues of blocks of flats from the communist era, and contemporary real estate development filling all the gaps between them. Lack of access to spatial data, unclear legal regulations and over-interpreted urban plan make nothing certain. The space is subject to constant negotiation and its users (inhabitants, administration, investors) try to shift the boundaries of their actions, bending the rules of the game. The fragmented space is filled with fences and hedges which surround even the buildings of public institutions.

The examples of cooperation that we can observe in the Romanian capital are mostly activist projects concerning the revitalization of public spaces and backyards. Sometimes local authorities are involved in these projects, testing various possibilities for supporting the development of social ties and improving the quality of public spaces. Private investors seem to be absent in this process, especially on the residential real estate market. Housing developments rarely offer added value in the form of semi-public spaces and infrastructure. In the conditions of a neoliberal economy, the cooperation of public administration, local community and private investors could bring solutions that satisfy the needs of all parties. However, it will require proper regulation, trust and mutual oversight.

Piața Obor

In the 2000s, Obor Square covered an area of 9,000 square meters filled with stalls and pavilions. Another 2,000 meters housed stores and restaurants. However, this space was no longer sufficient for the growing needs of its users. In 2005, the Municipality of Sector 2 of Bucharest decided to select a private investor for the market expansion project. Still an exception to the rule, the system of public-private partnership brought about the realization of a traditional market with modern infrastructure including a 4-story market hall and an extension with a year-round shopping center and underground parking.

The problem with public space between blocks of flats from before 1989 is mainly the lack of clear rules for its management and use. In order to protect the greenery from being destroyed by cars, residents of these buildings often block off more sections of lawns and squares. The Romanian Order of the Architects is working with local NGOs, municipal institutions and residents on the model solutions for several courtyards in Colentina. The ideas developed during the workshop were translated into a design strategy and guidelines for an architectural competition that will produce concrete solutions.

Colentina

Projects that engage residents in revitalizing urban space are also organized by studioBASAR. The pilot project “Urban Spaces in Action” was coordinated by a team consisting of architects, urban planners, social anthropologists and teachers. Through urban interventions based on the jointly constructed Urban Mobile Accumulator, the team collected information, communicated with the public, tested in real time the techniques of activating public space which functioned for several days as a place to meet.

Strada Dogarilor

Rational densification of the urban fabric may be an answer to the problem of urban sprawl, but it must respect the context and the interests of the local community. In the inner city of Bucharest, we can see very strong pressure from developers who buy plots of land, merge them in order to build much larger buildings, completely ignoring the historical urban layout.

The “Urban Spaces 1” building (designed by ADNBA) is an attempt to consciously intensify the urban fabric. Buidling tries to preserve the porosity of deep, narrow plots, while trying to capture the “collage” look of the surroundings. Badea Cartan is a similar project where it was possible to develop a semi-public courtyard. Neighboring large-scale Central residential complex stands in complete contrast to these two cases. The project shows all the consequences of non-negotiated public space for new, large developments. Located on the boundary of dense low-rise housing and prefabricated blocks of flats, it draws the worst features from these two contexts – excessive density, intensity and the height of the development.

Parcul Drumul Taberei

The problem of urban sprawl in Bucharest is primarily the tendency to locate new housing developments on the outskirts, just outside the administrative boundary of the city. Investors, taking advantage of the buyers’ lack of knowledge, poor management of the urban spaces and lack of regulation, offer small apartments in buildings of poor quality, in a very densely built-up area, limited only to the residential function. Such places lack social spaces, public squares or greenery to support the formation of a new community. The doubling of the area population in the last nine years results in chronic traffic jams, blocking an inefficient road network. Although Popeşti-Leordeni was initially considered a good housing option, the residents quickly became very dissatisfied with the quality of life. The endless expansion of the settlements also results in noise and pollution.

Popești-Leordeni

The park got its current form after the modernization carried out between 2013 and 2015. One of the smallest parks in Bucharest was renovated at a record cost of 17 million euros. Despite the costly renovation, some residents are disappointed with the end result due to the excessive use of artificial materials and a big amount of trees cut down for the upgrade. The abundantly watered and evenly trimmed lawns do not serve the park users. They are largely fenced off from the alleys, and the entire park is filled with the signs prohibiting various activities. The old and lush vegetation has been largely cut down, thus reducing the natural biodiversity of the park. The quality of construction of some elements was also controversial. Initially, the park’s alleys were made of resin-stabilized gravel, which began to fall apart soon after the park’s inauguration, requiring annual repairs.

Văcărești

In the 1980s, a decision to create an artificial water reservoir was made – 190 hectares of land was prepared and construction of the necessary reinforcements began. The overthrow of the communist regime meant that the grand infrastructural plans were abandoned, and since 1989 the area has gradually been reclaimed by nature. Its peaceful expansion was ensured by being cut off from the city and human presence with a five-meter-high concrete jetty and a fence.

The construction of the lake itself could not continue due to serious structural defects. In 2014, due to public pressure, Lake Văcărești gained the status of a protected area. Today it is one of the largest urban natural parks on the continent. The development of wildlife in the lake’s unfinished and inaccessible basin has led to the formation of a complex ecosystem, comparable to a river delta. In a city shaped largely by unclear regulations, where developers dictate the terms, the fact that such a large area has not been built-up is a rarity. So it turns out that it was not urban planning, but the lack of it and the abandonment of old plans that produced the best possible results.

Colophon

Organizer: Narodowy Instytut Architektury i Urbanistyki (National Institute of Architecture and Urban Planning, Poland)

Curatorial Team: Zuzanna Mielczarek, Kacper Kępiński

Partners: CANactions Festival, Ion Mincu University of Architecture and Urbanism, OARB (The Romanian Chamber of Architects Bucharest Subsidiary), Brno University of Technology – Faculty of Architecture, Instytut Polski w Kijowie (Polish Institute in Kyiv), Autoportret. Pismo o dobrej przestrzeni

Production: Weronika Sołtysiak

Communication: Dominik Witaszczyk, Joanna Krupa

Graphic Design: Victor Hardziuk, Martyna Wyrzykowska, Oleksandra Maiboroda

Project cooperation: Mania Bień (Scenography), Dagna Debiecka (3D models), Petro Vladimirov (Ukrainian part co-curating)

3D models: Wolf3D

Photography: Eva Drbalová (Brno), Kuba, Rodziewicz (Warsaw), Sasha Stavnichuk (Kyiv), Cristi Staicu, Kacper Kępiński, Zuzanna Mielczarek (Bucharest)

Video: Cristi Staicu (Bucharest), Jiří Choutka (Brno), Michał Sierakowski (Kyiv), Adrian Szadowiak (Warsaw)

Video production: Adrian Szadowiak (Shadow Media Group)

Local experts: Radek Toman, Bara Srpkova, Jiří Maly, Tereza Kvapilová (Brno)

Monika Konrad, Michał Oman, Marlena Happach, Joanna Erbel, Łukasz Drozda (Warsaw), Emil Ivănescu, Stefan Gheciulescu, Anca-Maria Pasarin, Maria Duda, Alexandru Belenyi (Bucharest), Oleksandr Animisov, Anastasiya Ponomaryova, Petro Vladimirov, Oleg Drozdov, Urbanyna, Igor Raikov (Ukraine).